Texas Modernism

The Grace Museum in Abilene is a gem of regional West Texas prairie town architecture. Originally the Grace Hotel, this historic building is reborn as an impressive art museum. One of the most interesting facets of the repurposed structure is the change of room height as one moves from floor to floor. The reduced ceiling height above the array of second floor galleries reminds me of the intimate viewing spaces encountered at the entry of the original Amon Carter in Ft. Worth.

As visitors ascend the majestic cast-iron and marble staircase from the first floor’s definitive exhibit, Seymour Fogel: On the Wall and Beyond, eyes are instantly attracted in all directions as the inviting galleries’ pictures project bursts of colors and shapes and motion of an unexpected variety of styles. The effect is quite striking and dramatic, as if the paintings’ very contents are exploding out of their frames, and out of the surrounding, darkened alcoves, toward the viewer all at once.

A long overdue celebration of early to mid-century Texas Modern painters, The Abstract Impulse presents a convincing tribute to these pioneering artists. Both the Seymour Fogel exhibit and The Abstract Impulse are co-curated by Judy Tedford Deaton and Katie Robinson Edwards. A catalog is in the works. This review will focus on but a few of the many Texas Modernist painters included in the exhibit.

‘Modern Art’ erupted around the globe at the same time, the first half of the 20th Century. Artists in Paris, Moscow, Mexico City, New York and Texas saw the same vision, Modern Abstract Art. Exploring new compositions, new forms, methods and media, these young artists pioneered abstract styles and developed contemporary synthetic paints for commercial applications, especially large public murals, funded by the WPA, most created on site in town and cities throughout the U.S. Most of the energy, creativity and prolific output of Texas Modernists went unnoticed by the national press. Art publications were written and printed on the east coast, and almost entirely about east coast artists.

Many Post WWII American artists were veterans, being educated in art schools around the country on the GI Bill. Many of the Texas artists in The Abstract Impulse exhibit secured art degrees from Texas colleges, aided by their veterans’ benefits. The world view of these returning soldiers was very different from before the war. They shared common horrid experiences and battlefield memories, but they also shared common hope for opportunity, invention, and new vision. Visually, for the museum visitor, this new way of seeing expands splendidly across the viewer’s full panorama as one climbs onto the second floor galleries of the Grace.

One of the Texas vets represented here is Robert Preusser (1919-1992). Presseur’s 1938 Stars and Circles remains one of the most-oft googled art images on the web. An oil on Masonite tour-de-force of cosmic emanations via color and contour, Stars and Circles has clearly struck a chord with a post 2001: a Space Odyssey, Star Wars, and Close Encounters generation. Presseur’s painting achieves an alluring veil of mostly organic, fluid forms, alive with bright, saturated colors, reminiscent of Paul Klee’s Sinbad series. Layers of light and dark tones move back and forth on the eye, with elaborate textural dances amongst the pulsating, chromatic feast.

Bill Reily’s noisy Ship Yard, of 1955, struck a loud, personal chord with me. A San Antonio artist, Reily may have been referencing the historic Beaumont Ship Yard. Ships were built at the famous port since before and during WWI, then became a vital source of sea-going war vessels in WWII, and continued to serve as major foundry and ship repair port well into the 1980’s. As a child, I have vivid memories of the Beaumont Ship Yard, a giant, blackened structure of stacked decks, machines, cranes, massive plates and pieces of iron and steel, all in motion, including the small, human workers moving about from level to level.

Reily’s Ship Yard is a beautiful confluence of monstrous industrial shapes and sea-level landscape. His pale shrimp-colored sky reminds me of Veneziano’s soft, pink backgrounds, though Reily’s filmy sky may more likely be the result of petroleum and East Texas wood-mill fumes in the air. His painting certainly captures the essential atmosphere of the messy hardware and trappings of a busy ship yard’s looming presence over the water’s edge.

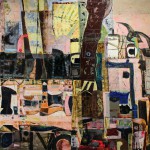

Ben L. Culwell’s paintings are like time capsules, repositories of traditional media and modern materials, all jumbled together: oil, resin, glass, sand, egg-tempera, rocks, and car-paint. There’s nothing timid or delicate about Culwell’s thick layers of textured materials, pushed, burned, shaped and scraped into fascinating polychrome collisions of geometric and organic forms. His complex constructions are deceptively hap-hazard looking. The work is dizzying, but exhilarating at the same time.

Recently, I joined friends Katie Edwards and Karl Williams to view the brutal sketchbooks of Ben Culwell. My first reaction to these amazing books was to be reminded of the dark, Beat, automatic anti-writings and anti-musings of William S. Burroughs. To experience a Culwell sketchbook is like witnessing an explosion in an alchemist’s shop: multitudes of odd, wild stuff blown in all directions. Culwell’s paintings and sketches could be the visual definition of the old surrealist method known as Cut-up. (Burroughs and his painter friend Brion Gysin are credited with reviving the Cut-up technique).

Jack Boynton was friend, mentor and teacher to a host of younger artists over many decades, including myself. Though Jack was prolific and his work relevant right through the year of his death (2010), it is appropriate that The Abstract Impulse displays a work completed when he was just twenty-four. Kites embodies both Jack’s facility with paint (even at a young age), and his sardonic take on life. Jack wasn’t cynical. He just didn’t waste time on pretense or small talk. His sense of humor could be severe, but he didn’t have an axe to grind. He observed everything, and constantly surprised friends with glaring examples of paradox and irony in even the most innocent-looking tableaus of life’s scenery.

Kites could be just that, or a reference to the bird. This would be in keeping with the theme of his other 1952 painting, Bird Trap. Katie Edwards discusses Bird Trap and its likely association with the spikey surrealism of Matta, in her seminal tome, Midcentury Modern Art in Texas (Univ. of Texas Press). Perhaps Kites depicts birds in the process of freeing themselves. Jack made images that cajoled or charmed viewers into studying a single unfamiliar form, pricking their curiosity into examining foreign icons or totems. The viewer isn’t sure if the object before them is something natural, or weird. Is it safe to approach? But with Jack’s ability to paint such inviting colors and tempting textures, the most reticent of viewers is lured into carefully observing even a spikey, suspicious thing.

Thomas Motley

A Review of The Abstract Impulse at the Grace Museum, Abilene, Texas, May 28-Oct. 24, 2015

Co-curated by Judy Tedford Deaton and Katie Robinson Edwards

All photos, courtesy, The Grace Museum

Robert Preusser, Stars and Circles, 1937-38, oil on masonite, The Summers Collection

Bill Reily, Ship Yard, 1955, oil on Board, The Summers Collection

Ben L. Culwell, Untitled, c. 1955, mixed media on masonite, Estate of Ben L. Culwell

Ben L. Culwell, Texan, 1957-1984, mixed media on board, The Summers Collection

Jack Boynton, Kites, 1952, oil on canvas, Harvell-Spradling Collection